It is a strange island and an enchanted one-our Isle of Man. It took many a thousand years and more before mankind discovered it, it being well known that the spirits of water, of earth, of air and fire did put on it an enchantment, hiding it with a blue flame of mist, so that it could not be seen by mortal eye. The mist was made out of the heat of a great fire and the salt vapor of the sea, and it covered the island like a bank of clouds. Then one day the fire went out, the sea grew quiet, and 10, the island stood out in all its height of mountains and ruggedness of coast, its green of fens and rushing of waterfalls. Sailors passing saw it. And from that day forth, men came to it and much of its enchantment was lost.

But not all. Let you know that at all seasons of the year there are spirits abroad on the Isle, working their charms and making their mischief. And there is on the coast, overhanging the sea, a great cavern reaching below the earth, out of which the devil comes when it pleases him, to walk where he will upon the Isle. A wise Manxman does not go far without a scrap of iron or a lump of salt in his pocket; and if it is night, likely, he will have stuck in his cap a sprig of rowan and a sprig of wormwood, feather from a seagull’s wing and skin from a conger eel. For these keep away evil spirits; and who upon the Isle would meet with evil, or who would give himself foolishly into its power?

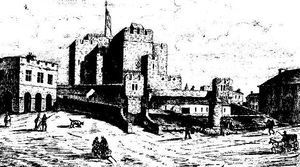

So it is that in the south upon the ramparts of Castle Rushen the cannon are mounted on stone crosses above the ramparts; and when a south Manxman knocks at his neighbor’s door he does not cry out, “Are you within?” But rather he asks, “Are there any sinners inside?” For evil is a fearsome thing, and who would have traffic with it?

I am long at beginning my tale, but some there may be who know little of our Isle, and a storyteller cannot always bring his listeners by the straightest road to the story he has to tell. This one is of the south, where the mists hang the heaviest, where the huts are built of turf and thatched with broom, where the cattle are small and the goats many, and where a farmer will tell you he has had his herd brought to fold by the fenodyree-a goblin that is half goat, half boy. But that is another tale.

Let me begin with an old Manx saying-it tunes the story well: “When a poor man helps another, God in his heaven laughs with delight.” This shows you that the men of Man are kind to one another, and God is not far from them even when the devil walks abroad. Count a hundred years, and as many more as you like, and you will come to the time of my story. Beyond Castletown in the sheading of Kirk Christ Rushen lived, then, a lump of a lad named Billy Nell Kewley. He could draw as sweet music from the fiddle as any fiddler of Man. When the Christmas time began, he was first abroad with his fiddle. Up the glens and over the fens, fiddling for this neighbor and that as the night ran out, calling the hour and crying the weather, that those snug on their beds of chaff would know before the day broke what kind of day it would be making. Before yule he started his fiddling, playing half out of the night and half into the day, playing this and playing that, carrying with him, carefully in his cap, the sprig of rowan and the sprig of wormwood, with the iron and salt in the pocket of his brown woolen breeches. And there you have Billy Nell Kewley on the Eve of St. Fingan.

Now over Castletown on a high building of cliff rises Castle Rushen. Beyond stands the oldest monastery on the Isle, in ruin these hundreds of years, Rushen Abbey, with its hundred treens of land. It was through the Forest of Rushen Billy Nell was coming on St. Thomas’ Eve, down the Glen to the Quiggan hut, playing the tune “Andisop” and whistling a running of notes to go with it. He broke the whistle, ready to call the hour: “Two of the morning,” and the weather: “Cold-with a mist over all,” when he heard the running of feet behind him in the dark.

Quick as a falcon he reached for the sprig in his cap. It was gone; the pushing through the green boughs of the forest had torn it. He quickened his own feet. Could it be a buggan after him-an ugly, evil one, a fiend of Man who cursed mortals and bore malice against them, who would bring a body to perdition and then laugh at him? Billy Nell’s feet went fast-went faster.

But his ear, dropping behind him, picked up the sound of other feet; they were going fast-and faster. Could it be the fenodyree-the hairy one? That would be not so terrible. The fenodyree played pranks, but he, having once loved a human maid, did not bring evil to humans. And he lived, if the ancient ones could be believed, in Glen Rushen. And then a voice spoke out of the blackness. “Stop, I command!”

What power lay in that voice! It brought the feet ofBilly Nell to a stop-for all he wanted them to go on, expected them to keep running. Afterward he was remembering the salt and iron in his pocket he might have thrown between himself and what followed so closely after him out of the mist. But he did nothing but stop-stop and say to himself: “Billy Nell Kewley, could it be the Noid ny Hanmey who commands-the Enemy of the Soul? And he stood stock still in the darkness, too frightened to shiver, for it was the devil himself he was thinking of.

He who spoke appeared, carrying with him a kind of reddish light that came from everywhere and nowhere, a light the color of fever, or heat lightning, or of the very pit ofhell. But when Billy Nell looked he saw as fine a gentleman as ever had come to Man-fine and tall, grave and stern, well clothed in knee breeches and silver buckles and lace and such finery. He spoke with grace and grimness: “Billy Nell Kewley of Castletown, I have heard you are a monstrous good fiddler. No one better, so they say.” “I play fair, sir,” said Billy Nell modestly.

“I would have you play for me. Look!” He dipped into a pocket of his breeches, and drawing out a hand so white, so tapering, it Inight have been a lady’s, he showed Billy Nell gold pieces. And in the reddish light that came from everywhere and nowhere Billy saw the strange marking on them. “You shall have as many of these as you can carry away with you if you will fiddle for me and my company three nights from tonight,” said the fine one.

“And where shall I fiddle?” asked Billy Nell Kewley. “I will send a messenger for you, Billy Nell; halfway up the Glen he will meet you. This side of Inidnight he will meet you.”

“I will come,” said the fiddler, for he had never heard of so much gold-to be his for a night’s fiddling. And being not half so fearful he began to shiver. At that moment a cock crew far away, a bough brushed his eyes, the Inist hung about him like a cloak, and he was alone. Then he ran, ran to Quiggan’s hut, calling the hour: “Three of the clock,” crying the weather: “Cold, with a heavy Inist.”

The next day he counted, did Billy Nell Kewley, counted the days up to three and found that the night he was to fiddle for all the gold he could carry with him was Christmas Eve. A kind of terror took hold of him. What manner of spirit was the Enemy of the Soul? Could he be anything he chose to be-a devil in hell or a fine gentleman on earth? He ran about asking everyone, and everyone gave him a different answer. He went to the monks of the abbey and found them working in their gardens, their black cowls thrown back from their faces, their bare feet treading the brown earth.

The abbott came, and dour enough he looked. “Shall I go, your reverence? Shall I fiddle for one I know not? Is it good gold he is giving me?” asked Billy Nell. “I cannot answer anyone of those questions,” said the abbott. “That night alone can give the answers: Is the gold good or cursed? Is the man noble or is he the devil? But go. Carry salt, carry iron and bollan bane. Playa dance and watch. Play another-and watch. Then play a Christmas hymn and see!”

This side of midnight, Christmas Eve, Billy Nell Kewley climbed the Glen, his fiddle wrapped in a lamb’s fleece to keep out the wet. Mist, now blue, now red, hung over the blackness, so thick he had to feel his way along the track with his feet, stumbling.

He passed where Castle Rushen should have stood. He passed on, was caught up and carried as by the mist and in it. He felt his feet leave the track, he felt them gain it again. And then the mist rolled back like clouds after a storm and before him he saw such a splendid sight as no lump of a lad had ever beheld before. A castle, with courtyard and corridors, with piazzas and high roofings, spread before him all aglowing with light. Windows wide and doorways wide, and streaming with the light came laughter. And there was his host more splendid than all, with velvet and satin, silver and jewels. About him moved what Billy Nell took to be highborn lords and ladies, come from overseas no doubt, for never had he seen their like on Man.

In the middle of the great hall he stood, unwrapping his fiddle, sweetening the strings, rosining the bow, limbering his fingers. The laughter died. His host shouted:

“Fiddler, play fast-play faster!”

In all his life and never again did Billy Nell playas he played that night. The music of his fiddle made the music of a hundred fiddles. About him whirled the dancers like crazy rainbows: blue and orange, purple and yellow, green and red all mixed together until his head swam with the color. And yet the sound of the dancers’ feet was the sound of the grass growing or the corn ripening or the holly reddening-which is to say no sound at all. Only there was the sound of his playing, and above that the sound of his host shouting, always shouting: “Fiddler, play fast-play faster!”

Ever faster-ever faster! It was as with a mighty wind Billy Nell played now, drawing the wild, mad music from his fiddle. He played tunes he had never heard before, tunes which cried and shrieked and howled and sighed and sobbed and cried out in pain. “Play fast-play faster!” He saw one standing by the door-a monk in a black cowl, barefooted, a monk who looked at him with deep, sad eyes and held two fingers of his hand to his lips as if to hush the music.

Then, and not till then, did Billy Nell Kewley remember what the abbott had told him. But the monk-how came he here? And then he remembered that too. A tale so old it had grown ragged with the telling, so that only a scrap here and there was left: how long ago, on the blessed Christmas Eve, a monk had slept through the midnight Mass to the Virgin and to the newborn Child, and how, at complin on Christmas Day, he was missing and never seen again. The ancient ones said that the devil had taken him away, that Enemy of All Souls, had stolen his soul because he had slept over Mass.

Terror left Billy NelL He swept his bow so fast over the strings of his fiddle that his eyes could not follow it. “Fiddler, play fast-play faster!” “Master, I play faster and faster!” He moved his own body to the mad music, moved it across the hall to the door where stood the monk. He crashed out the last notes; on the floor at the feet of the monk he dropped iron, salt, and bollan bane. Then out of the silence he drew the notes of a Christmas carol-softly, sweetly it rose on the air:

Adeste, fideles, laeti, triumphantes, Venite, venite in Bethlehem: Natum videte, Regem angelorum: Venite, adoremus, venite, adoremus, Venite, adoremus Dominum.

Racked were the ears of Billy Nell at the sounds which surged above the music, groans and wailing, the agony of souls damned. Racked were his eyes with the sights he saw: the servants turned to fleshless skeletons, the lords and ladies to howling demons. And the monk with the black cowl and bare feet sifted down to the grass beneath the vanishing castle-a heap of gray dust. But in the dust shone one small spark of holy light-a monk’s soul, freed. And Billy Nell. took it in his hand and tossed it high in the wind as one tosses a falcon to the sky for free passage. And he watched it go its skimming way until the sky gathered it in.

Billy Nell Kewley played his way down the Glen, stopping to call the hour: “Three of this blessed Christmas morning,” stopping to cry the weather: “The sky is clear … the Christ is born.”

In case no one knows, this version comes from the wonderful collection of traditional Christmas tales by the great storyteller Ruth Sawyer The Long Christmas. In the collection it is called “Fiddler play fast, play faster”. The collection is long out of print, but you might be able to find an ex-library copy about the place. It’s worth the hunt, if you love traditional Christmas tales.